A Few Thoughts on Saint Joseph’s History, from Vicar Lauren:

Too often, parish histories are either boring or prettied up; too often, they’re all about the building and clergy, and attend too little to all the other people who make up a church, and what they do inside and outside that building.

Also, too often local church history presents itself as a straightforward set of facts those of us in the present day simply acquaint ourselves with (or not).

But I prefer to think of church history as a spiritual practice—in the words of historian and librarian Margaret Bendroth, “the spiritual practice of remembering.” History as verb, as much as history as noun. History as an umbrella for research and study, but also for celebration, thanksgiving, repentance, and lament.

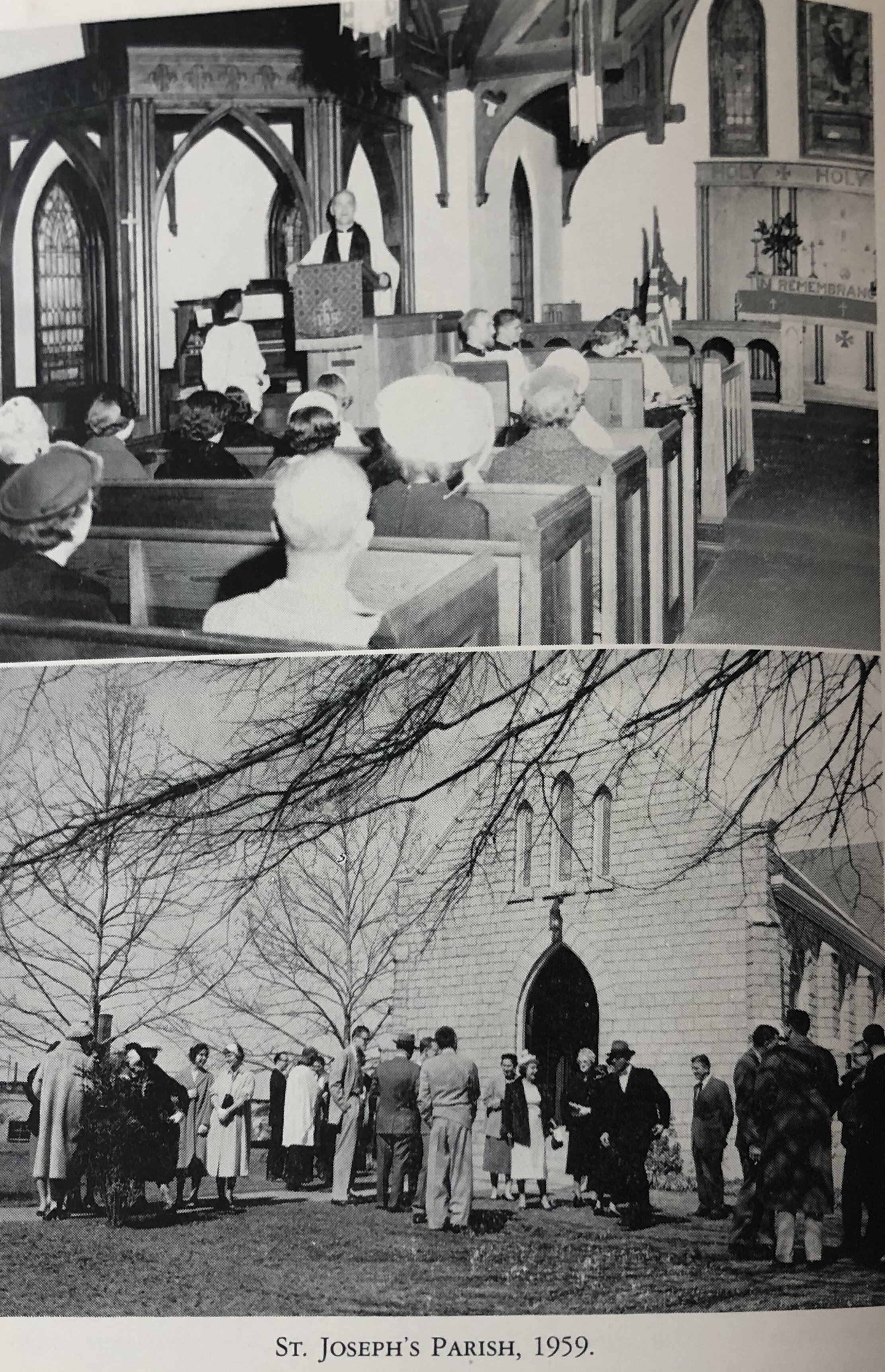

The staid, institutional version of the history at St Joe’s begins something like this: In 1894, William Erwin began to teach Sunday School classes for his employees – and that Sunday School became a mission of St. Philip’s Episcopal four years later. Originally, the congregation met (in the words of our earliest published parish history) in “in a wooden hall over a combination store-post office owned by the mill.” The church building that still stands today was completed in 1908.

Lurking underneath even those few sentences, of course, is a fair amount of intrigue: insofar as St Joe’s was first a church for textile mill workers, founded by the mill manager, meeting first in a building owned by the mill, complicated questions about power and paternalism were present from the very founding of St. Joseph’s.

Mill churches were a significant feature of the ecclesial landscape of early twentieth-century North Carolina. As the Episcopal bishop of North Carolina, Joseph Blount Cheshire, observed in 1907 “the great increase of manufactures in North Carolina had developed a new and interesting class of missions, demanding our intelligent and liberal support.” A classic study of Christianity in Southern mill towns, Liston Pope’s Millhands and Preachers (1942), observed that clergy were often silent in the face of textile mills’ exploitation of laborers. (Consider the words of one South Carolina textile owner Pope quotes: “We had a young fellow from an Eastern seminary down here as a pastor a few years ago, and the young fool went around saying that we helped pay the preachers’ salaries in order to control them. That was a damn lie—and we got rid of him.”) How did St. Joe’s leaders and congregations engage the prevailing culture – including the mills’ norms around labor? I look forward to our uncovering this.

Before I trained to be an Episcopal priest, I trained to be an American historian. One of the first things I do when I land in a new place is try to learn its history – a process that, of course, takes years. Questions about the texture of being a “mill church” will be among the first I’ll be digging into as I seek to learn more about the history of St. Joe’s. In addition to Pope, here’s some of what I’ll be reading to help me pursue those questions – let me know if you want to join me: Spindles and Spires by John R. Earle, Dean D. Knudsen, and Donald W. Shriver, Jr., Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Mill World by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, et al., and From Paternalism to Protest: Labor Relations in a Southern Textile Mill Community by Tiffany Franke. In my fantasy, I discover notes to Mr. Erwin’s Sunday school classes in a long-ignored Durham attic.

*

Buildings and clergy are, of course, not uninteresting.

St Joe’s church was built from Rowan County granite. As historian and erstwhile St. Joe’s vicar Rhonda Mawhood Lee recently pointed out to me, that indicates something about how much Erwin was willing to spend on the church. “Even Francis Murdoch, the textile magnate who paid for the construction of several mission churches in and around Rowan County itself,” Rhonda noted, “only ponied up for frame or brick.” And it's instructive to contrast the amount of money tied up in St. Joe’s building (“one of the handsomest little buildings in North Carolina,” sang a 1908 newspaper account of the building’s consecration; “One has rarely seen a more beautiful design…. The stone work is perfect, and the first thought of its promoters was to put the best material possible in it”) with the material resource available to the congregation of St. Titus, purchasing their first property just a few years later. As Rhonda’s research into diocesan history unearthed, St. Titus’s two buildings and lot cost $1,700. I have yet to track down exactly how much was spent on St. Joe’s building, but the September 1912 issue of Stone: A Monthly Publication Devoted to the Stone Industry in All of Its Branches reports on Rowan County’s decision to build its courthouse out of local granite (“at a considerable increase over the price of brick”), and that report provides suggestive context about the cost of St Joe’s church: “By using granite the [courthouse] will cost $111,100.” The topic of church buildings and their materials is the stuff of social history. Surely St Joe's small sanctuary cost nowhere near $111,100. But surely its budget also dwarfed what St Titus could spend. If, as that aforementioned newspaper article has it, “everything about [St Joe’s granite church building] corresponds finely with the devotion of its builder, Mr. W. A. Erwin,” it also corresponds finely with the long history of racist wealth disparities and the Episcopal Church’s participation therein.

As for clergy, our most storied priest is John Shelby Spong. Spong, who eventually became the Bishop of Newark (New Jersey), was something of a national figure in the 1980s and 1990s, both because of his advocacy on behalf of gay and lesbian Episcopalians, and because of his controversial theological commitments, which strayed far from creedal Christianity (he argued, for example, that “Understanding God in theistic categories …is no longer believable” so “Most God talk in liturgy … has thus become meaningless”). The first published history of St Joe’s, written just a few years after Spong’s tenure here, noted breathlessly that Spong’s “contagious enthusiasm played a large part in an upsurge in enrollment during his ministry – one characterized by an aliveness in teaching and preaching. During the Rev. Mr. Spong's ministry at St. Joseph's, many physical improvements were made in the Church edifice. New lighting fixtures and air conditioning in the Church were installed. New flooring was installed in the Parish House.” In Spong’s autobiography, Here I Stand (the title quotes Martin Luther, and thereby compares Spong’s achievements to those of one the sixteenth century’s great reformers), Spong writes that “St. Joseph's Church stood physically between the east campus of Duke University and the Erwin Cotton Mill in West Durham,” and that the “congregation straddled both worlds,” university and mill. Writing in 2000, Spong was interested in the dynamics of early twentieth-century mill churches. He recalled being told this story about William Erwin’s relationships with the mill workers who lived in West Durham: “Mr. Erwin…wanted his mill workers to attend his church….In his effort to build the confirmed membership of his church, Mr. Erwin organized a contest among his employees to see which side could get the most new members. He picked two of his foremen to be captains of the respective blue and red teams. Every candidate for confirmation received a watch.…By the time I arrived at St. Joseph's, Mr. Erwin was but a memory and most of these storied candidates for confirmation had, with watches on their arms, returned to the churches of their own preference, but a core of the mill community was still present.”

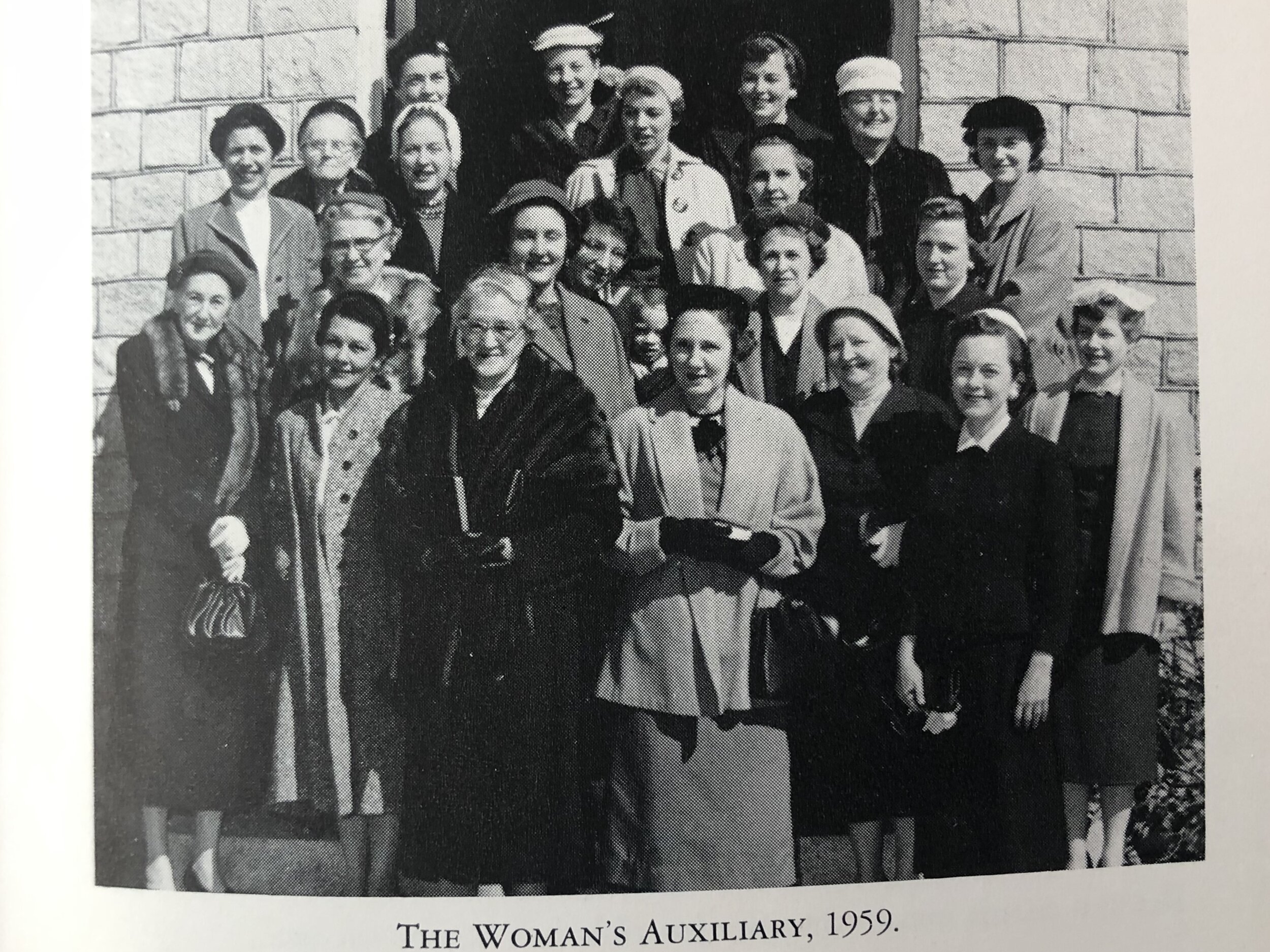

A rich and complex history, then, has our small St. Joseph’s. And I, at least, have much to learn – I know less than I wish about the specific ways that St. Joe’s underwrote Jim Crow, in those years when Spong was preaching and before, or how it engaged the civil rights movement; about the specific contributions women made to raising money for the church (I have learned from parishioner Muriel Mellown’s St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church: The Second Fifty Years that in 1966, the first women, Joyce Avery and Susana Berry, joined the church vestry); about what the parish and its prayers meant to parishioners in 1901 or 1940. All this and much more, I look forward to discovering.

Here, for your perusal, is St. Joseph’s Church: Fifty Year of Service, 1908-1958 and Mellown’s St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church: The Second Fifty Years. Reading the first volume, I was struck by this: in 1958, the writer of the history looked back on the lot of St. Joe’s in the mid-1930s—it was the midst of the Great Depression, and it was shortly after the deaths both of Erwin and of a beloved priest—and saw the church at a turning point. “St. Joseph's, almost in its 25th year faced the task of almost starting over again,” of “rebuild[ing].” That sentence might not have seemed noteworthy had I read it three years ago. But in the wake of Covid, all churches are in a way starting again. The spiritual practice of remembering, I hope, will be part of ours.